Introduction: A Rare Rash With a Familiar Lesson

Rupioid psoriasis is not the kind of dermatologic diagnosis that appears casually on a busy clinic day. It is visually dramatic, biologically intense, and clinically demanding. The lesions are thick, hyperkeratotic, and layered—often described as “limpet-shell” crusts—making them more reminiscent of infectious dermatoses than classic plaque psoriasis. When rupioid morphology appears, it immediately raises the stakes: clinicians must rule out syphilis, HIV, scabies, and other mimickers before settling on a psoriatic diagnosis.

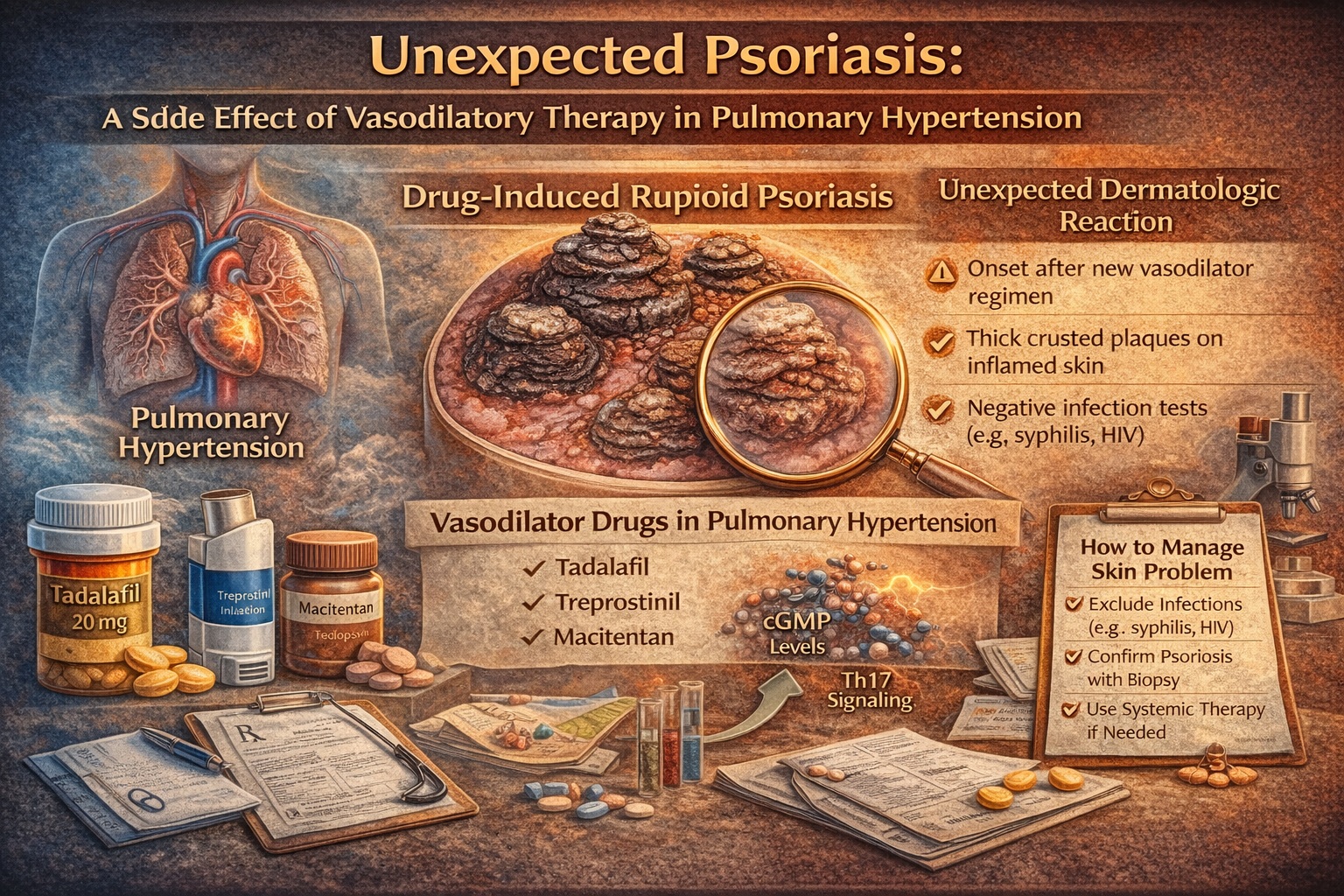

The case report behind this article describes a striking clinical scenario: a woman with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) develops new-onset disseminated rupioid psoriasis after starting a potent vasodilatory regimen. The medications—treprostinil, macitentan, and tadalafil—are not obscure. They are increasingly used in advanced PAH management. The eruption is rare, but the lesson is highly reusable: when a rash is unusual, always suspect the medication list—especially when the regimen changes coincide with onset.

Modern medicine has created a paradox. We are excellent at building effective multidrug regimens for complex systemic disease, yet we remain vulnerable to “side effects that don’t read the same textbook chapter.” Dermatology frequently becomes the messenger. The skin, inconveniently visible, often reports systemic immune imbalance before any lab test does.

This article explains rupioid psoriasis in practical clinical terms, examines why vasodilatory therapy might plausibly precipitate it, and offers clinician-level strategies for diagnosis and management—particularly when stopping the suspected drugs is not an option.

Rupioid Psoriasis: What It Is and Why It Demands Respect

Rupioid psoriasis is best understood as psoriasis under maximal inflammatory pressure. The lesions are thick, conical plaques with adherent crusts formed by hyperkeratosis mixed with serous exudate. Unlike the smoother silvery scale of typical plaque psoriasis, rupioid lesions look heavy, layered, and “constructed.” In the case report, the lesions were disseminated and involved trunk, extremities, flexures, genital and groin regions, and plantar feet—an anatomic distribution that creates both medical and functional distress.

Clinically, rupioid morphology is a diagnostic trap if handled carelessly. Because rupioid lesions are also seen in secondary syphilis and other infectious or immunosuppressive contexts, clinicians must actively exclude those etiologies rather than assuming psoriasis from appearance alone. In the reported case, syphilis and HIV testing were negative, which is exactly the kind of step that separates thoughtful medicine from confident guessing.

Histopathology remains the anchor. The biopsy in the case showed classic psoriatic features: epidermal hyperplasia, compact hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, hypogranulosis, suprapapillary thinning, dilated dermal vessels, and neutrophils in the stratum corneum—features consistent with psoriasis rather than infection. The microphotographs and the described biopsy findings on page 3 illustrate this convincingly (neutrophils in stratum corneum, psoriasiform hyperplasia, and vascular dilation).

In short: rupioid psoriasis is a rare variant, but it follows psoriatic biology. Its importance lies in what it implies—marked inflammation, significant dysregulation, and the need to search for triggers.

The Case Pattern: Timing, Distribution, and the “New Regimen” Signal

The patient was a 69-year-old woman with PAH who developed a 3-month history of widespread hyperkeratotic crusted plaques. Crucially, her PAH treatment regimen—treprostinil, macitentan, and tadalafil—had been started 12 months before the skin eruption, with therapeutic levels reportedly achieved six months prior. This timeline matters because drug-provoked psoriasis does not always appear immediately; delayed onset is well documented.

Equally important is what was absent: no personal or family history of psoriasis, no joint symptoms, no mucosal involvement, and negative infectious screening. In clinical reasoning, absence is not proof—but it changes probability. When an older patient develops abrupt, severe, disseminated rupioid psoriasis without prior psoriatic history, the clinician should actively consider external triggers: medications, systemic inflammation, stress, infections, or immune shifts.

The distribution and morphology were striking: thick sero-exudative crusts and concentric layered scale. The case images (Fig 1 described on page 2) emphasize the concentric, layered “shell-like” scale. That morphology, paired with widespread involvement including flexures and genital areas, is not typical “mild psoriasis.” It is a severe inflammatory phenotype.

A practical clinical implication follows: when the eruption is severe, do not waste time on minimalist treatment. Topical monotherapy rarely suffices. The reported patient responded well to systemic methotrexate plus topical calcipotriene/betamethasone foam, improving significantly within two months and maintaining remission after tapering—an outcome that underscores that even dramatic psoriasis variants can be controlled with correct intensity.

Mechanistic Plausibility: How Vasodilators Might Push Psoriatic Biology Over the Edge

At first glance, “vasodilators causing psoriasis” sounds like a mismatch of organ systems. But psoriasis is not merely a keratinocyte problem—it is a vascular and immune disease expressed through skin. Psoriatic plaques demonstrate increased vascularity and altered cutaneous blood flow dynamics. The paper cites evidence that psoriatic plaques have higher baseline blood flow and exaggerated responses to vasodilatory provocation compared with uninvolved skin, likely due to superficial vessel expansion and deeper arteriolar abnormalities.

Now consider the patient’s regimen: three medications that, through different mechanisms, amplify vasodilation and vascular signaling. Tadalafil increases cGMP by inhibiting PDE5. Treprostinil is a prostacyclin analog that signals through prostanoid receptors and influences immune pathways. Macitentan blocks endothelin receptors, affecting vasoconstriction and potentially inflammatory cascades.

The tadalafil angle is particularly interesting. Psoriatic epidermal hyperplasia has been linked to increased cGMP levels and a reduced cAMP/cGMP ratio. cAMP and cGMP have opposing effects on epidermal proliferation, with cGMP potentially promoting proliferative activity. This provides a plausible pathway by which sustained cGMP elevation might support a hyperproliferative epidermal state in susceptible contexts.

Treprostinil adds immune complexity. The report discusses downstream effects that can enhance pathogenic Th17-mediated immune responses, a core axis in psoriasis pathogenesis. Even if treprostinil may also signal through cAMP pathways with theoretical anti-proliferative effects at the keratinocyte level, the net effect could still be pro-psoriatic if immune activation and nonspecific vasodilation outweigh keratinocyte-protective signals.

Macitentan is perhaps the most ironic player. Endothelin-1 signaling can promote keratinocyte proliferation and inflammatory cascades, so endothelin receptor antagonism might be expected to be anti-psoriatic. Yet the report proposes that strong systemic vasodilation or complex receptor dynamics (including differences between ETA and ETB effects on dendritic cell immune activity) may override theoretical protective pathways. The skin, as usual, refuses to behave like a simple receptor chart.

The honest conclusion is the one the authors themselves emphasize: causality cannot be proven here because the regimen was not modified. But plausibility is high enough to matter clinically—especially because such regimens are increasingly used.

Diagnosis and Management: How to Handle Rupioid Lesions Without Panic or Delay

Rupioid lesions should trigger a disciplined diagnostic approach. The first goal is to rule out key infectious mimickers and immunosuppressive contexts. In this case, syphilis and HIV were ruled out with negative serologies, and the patient was immunocompetent. That step is not optional; it is core clinical safety.

The second goal is to confirm psoriasis histologically when morphology is atypical. A biopsy showing psoriasiform changes and neutrophils in the stratum corneum supports rupioid psoriasis rather than a crusted infection. The biopsy findings described (and illustrated in Fig 2 on page 3) provide that confirmation.

The third goal is to assess drug causality realistically. In many suspected drug-provoked psoriasis cases, discontinuation is possible and often attempted. Here, cardiopulmonary consultation advised against modifying PAH medications—an entirely reasonable decision in severe PAH, where regimen stability can be life-preserving. This scenario is common: you cannot always stop the suspected trigger. Dermatology must then treat the consequence without destabilizing the primary disease.

Treatment in this patient involved systemic methotrexate 15 mg weekly with folic acid supplementation plus topical calcipotriene/betamethasone foam. Improvement was significant within two months, and the patient remained asymptomatic after tapering. This response suggests that even when the suspected trigger persists, aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy can restore control.

From a practical standpoint, clinicians should treat rupioid psoriasis like severe psoriasis: systemic therapy is often required, topical therapy supports barrier repair and symptom control, and monitoring must be real—especially in older patients.

What Clinicians Should Do Differently: A Practical Playbook

The key clinical takeaway is not “avoid vasodilators.” PAH therapy is not elective. The takeaway is “anticipate unusual immune/skin responses and document them early.” A thorough medication history should be standard for any rupioid eruption, because drug-provoked psoriasis may appear weeks to months after initiation and is not limited to classic culprits like lithium or beta-blockers.

Clinicians managing PAH should be alert to new inflammatory skin disease after regimen changes, especially when multiple vasodilatory mechanisms are introduced simultaneously. Patients may not volunteer skin symptoms early, particularly if they assume it is an allergy or “just dry skin.” Asking once at follow-up can prevent months of uncontrolled inflammation.

Dermatologists and primary physicians should remember that when discontinuation is not possible, treatment must focus on controlling skin inflammation without undermining cardiopulmonary stability. Methotrexate worked well in this case; other systemic psoriasis therapies could be considered depending on comorbidity, contraindications, and access, but the core principle is: do not undertreat severe morphology.

- A clinician’s checklist for rupioid eruptions

- Rule out infectious mimickers (especially syphilis and HIV) and assess immunosuppression risk.

- Obtain a biopsy when morphology is atypical or disseminated.

- Perform a full medication timeline review (new drugs in the last 3–18 months matter).

- Decide early whether suspected drugs can be modified; if not, escalate psoriasis therapy appropriately.

- Use clear patient instructions to reduce secondary infection risk from fissuring, scratching, and barrier failure.

This approach prevents “diagnostic drift,” where patients cycle through topical steroids and antifungals for months before someone finally performs the necessary biopsy and history review.

Conclusion: A Case Report That Improves Real-World Medicine

This case illustrates a clinically important point: severe vasodilatory regimens—particularly combinations used for pulmonary arterial hypertension—may plausibly precipitate rare inflammatory skin reactions, including rupioid psoriasis, even in patients without personal or family psoriatic history.

The mechanisms are likely multifactorial: cGMP elevation (tadalafil), immune pathway modulation with potential Th17 enhancement (treprostinil), complex endothelin receptor biology (macitentan), and a vascular environment primed for exaggerated cutaneous blood flow responses. None of this proves causality, but it strongly supports vigilance.

Most importantly, the case demonstrates that effective dermatologic control is achievable even when the suspected triggers cannot be discontinued. Methotrexate combined with topical therapy produced full clinical resolution within weeks. The outcome is reassuring: the skin can be calmed without endangering PAH therapy.

The final irony is gentle but unavoidable: the medications were designed to improve blood flow and keep a patient alive—yet the skin responded as if it had received a personal insult. This is not a failure of therapy; it is a reminder that human biology is a network, not a menu of isolated organs.

FAQ

1. Is rupioid psoriasis always caused by drugs or immunosuppression?

No. Drug triggers and immunosuppression are important considerations, but rupioid psoriasis can be idiopathic. The key is to rule out infectious mimickers and evaluate triggers rather than assuming a single cause.

2. Should PAH vasodilator therapy be stopped if rupioid psoriasis appears?

Not automatically. In severe PAH, stopping therapy may be unsafe. Multidisciplinary decision-making is essential. Often the best strategy is to continue life-preserving therapy while aggressively treating psoriasis.

3. What is the most important first step when rupioid lesions are seen?

Exclude key infections (especially syphilis and HIV) and confirm diagnosis with biopsy when appropriate. Rupioid morphology is a diagnostic warning sign, not a cosmetic detail.